Authors

- Dorothy N.S. Chan, RN, PhD; The Nethersole School of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

- Bernard M.H. Law, PhD; The Nethersole School of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

- Winnie K.W. So, RN, PhD, FAAN; The Nethersole School of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

- Ning Fan, MBBS; Yan Chai Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR, China

Cervical cancer screening utilisation is known to be of benefit to reduce the prevalence of cervical cancer,1 one of the most common cancers among women. However, individuals with physical disabilities, including those having impairments in mobility, vision and hearing, were reported to exhibit low cervical cancer screening utilisation rate.2,3 This renders them more likely to have missed the opportunities to detect any precancerous lesions early for a timely treatment that prevents these lesions to develop into cancer. Therefore, strategies need to be developed to increase the screening rates of individuals with physical disabilities. To do so, we need to have a better understanding on the factors that hamper and facilitate these individuals to undergo cervical cancer screening.

To this end, our team had previously conducted a systematic review exploring the barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer screening utilisation among individuals with mobility, visual and hearing impairments. Based on these identified barriers and facilitators, we aim to make recommendations on the potential strategies that help increase the screening rates of these disadvantaged individuals.

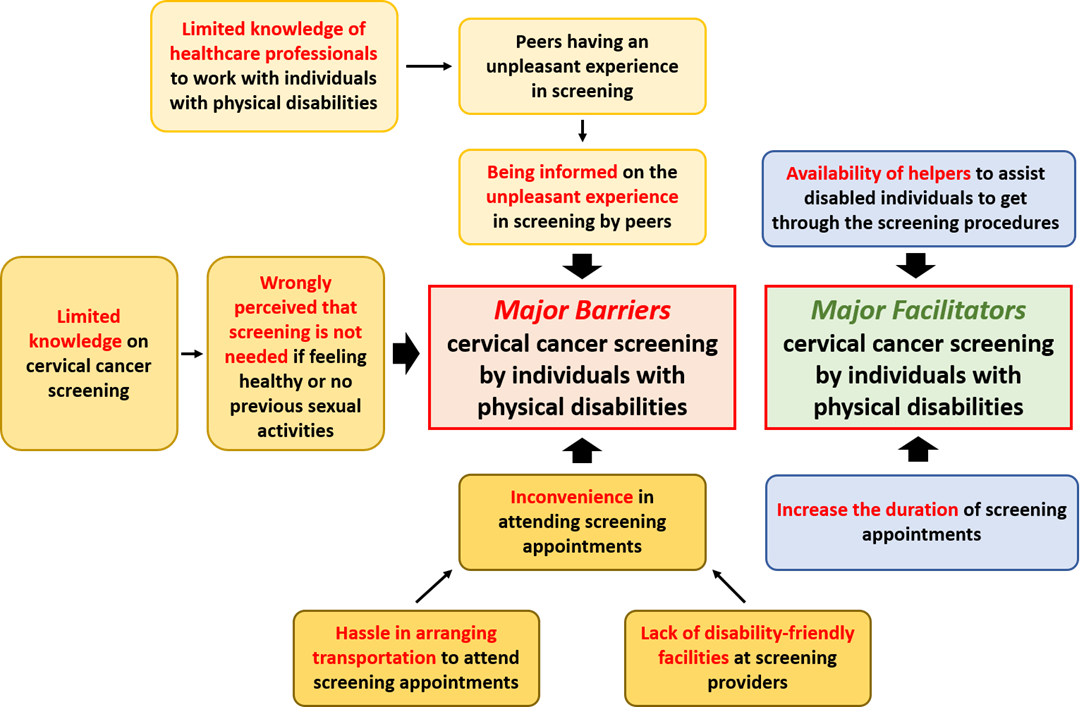

Overall, people with physical disabilities, especially those with mobility disabilities, are hampered to undergo cervical cancer screening by three major factors:

• They possess limited knowledge, and even misconceptions, on the need for screening – they believe that screening is not needed if they feel healthy or are not sexually active.

• They perceive that undergoing screening is an unpleasant experience, as they have been informed on the poor screening experience of their peers, potentially due to the lack of knowledge of healthcare professionals to work with people with disabilities.

• They experience difficulties in accessing screening providers, especially owing to the hassle in making transportation arrangements and the lack of ramps for wheelchairs within the premises of screening providers.

On the other hand, individuals with physical disabilities would be more likely to undergo cervical cancer screening if an attendant is on hand to help these individuals throughout the screening procedures, and that the duration of screening appointments can be lengthened so that they can feel less rushed during the screening process.

The review findings enable the suggestion of several strategies for enhancing the cervical cancer screening utilisation rate of individuals with physical disabilities. First, public education on cervical cancer screening should be enhanced within communities, through the implementation of educational programmes that help clarify certain misconceptions on cervical cancer screening possessed by the public. Second, more resources may be allocated to train healthcare professionals to work with people with disabilities, enabling these healthcare professionals to be more patient with these disabled individuals. This may provide a more pleasant and relaxing experience for these individuals to undergo screening. Third, screening providers may also consider allocating resources to employ helpers assisting individuals with physical disabilities to get into position for the screening procedures, install disability-friendly facilities at their premises and provide transportation services for these individuals, offering them a greater level of convenience for them to attend screening appointments. All these may enhance the intention and capability of these individuals to undergo screening.

The article reporting the methodologies and findings of this review was recently published in Health Policy.4

References

1. Landy R, Sasieni PD, Mathews C, Wiggins CL, Robertson M, McDonald YJ, Goldberg DW, Scarinci IC, Cuzick J, Wheeler CM; New Mexico HPV Pap Registry Steering Committee. Impact of screening on cervical cancer incidence: A population-based case-control study in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2020; 147(3): 887-896. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32826.

2. Lofters A, Guilcher S, Glazier RH, Jaglal S, Voth J, Bayoumi AM. Screening for cervical cancer in women with disability and multimorbidity: a retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ Open. 2014; 2(4): E240-E247. http://dx.doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20140003.

3. Kellen E, Nuyens C, Molleman C, Hoeck S. Uptake of cancer screening among adults with disabilities in Flanders (Belgium). J Med Screen. 2020; 27(1): 48-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0969141319870221.

4. Chan DNS, Law BMH, So WKW, Fan N. Factors associated with cervical cancer screening utilisation by people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Health Policy. 2022: (in press). doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.08.003.

A schematic diagram depicting the identified barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer screening utilisation among people with physical disabilities.